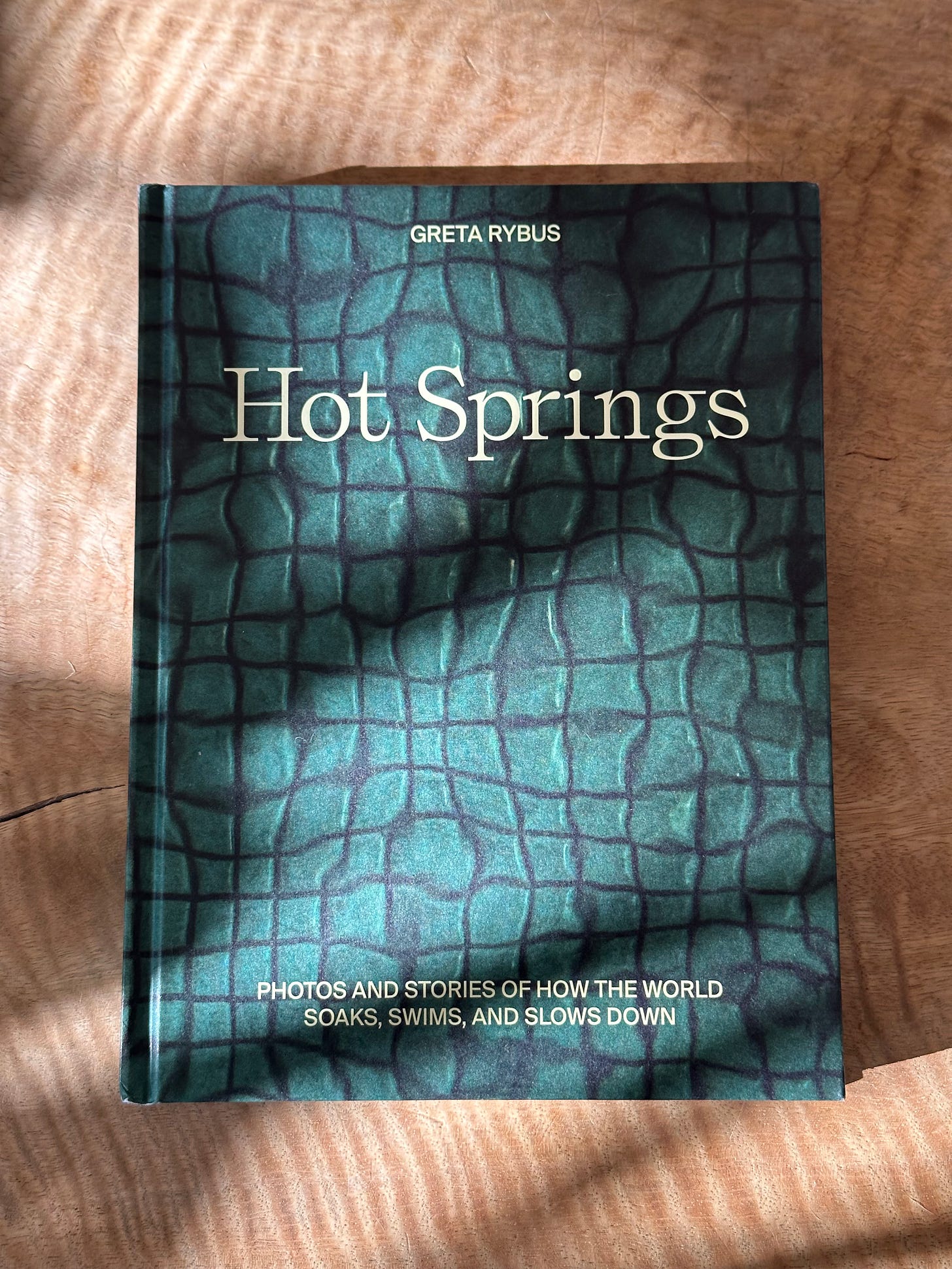

Stone Speaks With Artist, Greta Rybus

In A Dialogue Centering Around Her New Book Hot Springs, We Explore Water As Muse, Mother, Teacher, & Resource

Last week I had the pleasure of speaking with Greta Rybus, author of Hot Springs: Photos And Stories Of How The World Soaks, Swims, And Slows Down. The book gathers the stories of 23 bathing places across twelve countries, exploring themes of collectivism, land use, culture, tradition, sociology, folklore, history, etc.

Greta shares, “I grew up going to wild hot springs in Idaho, and spent two years in Japan as a teenager visiting local onsen and municipal baths. The contrast between the different ways of experiencing geothermal water intrigued me. I began researching and pitching this book six years ago. It was a dream come true to adventure around the world for this book: taking photos, talking with people, and being in hot water. I found kindness and interesting stories everywhere I went.”

It was incredible to listen to Greta delve deep into her lifelong journey with hot water, dating back to her grandmother’s water journals of 1873. This archive catalogues her family’s travels around Yellowstone during the time when it first became a national park. As I listened to Greta share, I was so entranced with the way she takes in her surroundings — there was such a layered nuance to every detail. I felt as though I was transported with her to the onsen she visited while living in Japan as a teenager, being educated by an elder on how to wash before entering a sacred space. A gifted artist, listener, and storyteller, Greta softly emphasizes water’s powerful role in supporting the cultivation of primal and intuitive human connection. Unafraid to tackle sensitive subjects, she slips into spaces and seamlessly becomes apart of that environment.

I highly recommend this woman’s work & as per her request, should you wish to purchase Hot Springs (you definitely should) please do so from your local bookstore! To learn more about her upcoming projects, please visit the links below & enjoy the dialogue X j.

Hierápolis-Pamukkale | Image © Greta Rybus

“Like a lot of hot springs and natural wonders, Pamukkale has been in danger of being loved to death. In old photos, the blue pools brim with water that spills abundantly down each level. Now, only a fraction of its pools are still filled—the rest are protected after decades of weather changes and overuse. There are several gift shops with magnets and books and postcards. Cafés sell corn, fresh-squeezed orange juice, ice cream, and sandwiches. Tour groups spill out of massive white buses and gather at the edge of the cotton palace, they walk over its rippled surface and soak their feet and bodies in the lukewarm water. Some pay the extra fee to bathe in the Ancient Pool, to swim where Cleopatra may have once soaked. I imagined her in the pool, with the columns still holding up a stone ceiling. Light must have filtered in, dappling the water in beams. Did she bathe with the lover who gave it to her? With friends? Alone? Was she ever there at all?

It was a strange feeling to walk on the same floor tiles as stately citizens from an ancient city. Everything I did suddenly felt unreasonable and uncouth, like the squeaking sounds of my sandals and the silly song I had stuck in my head. I thought of them; their search for healing and pleasure was the same as mine. They sought relief, excitement, love, clarity. We’d arrived at the same place.”

Gellert Baths, Budapest | Image: © Greta Rybus

Image Caption: “Each hot springs story starts deep underground, where groundwater or rainwater trickles through subterranean faults and fissures, mingling with magma and heated rocks. Pressure forces the heated vapors and liquids upward, back toward the surface. It can take the form of geysers, fumaroles, and mud pots. Sometimes, miraculously, it creates hot, mineral-rich water of various temperatures and temperaments, some perfect for humans to soak in.

To soak in a hot spring is to be cradled and cared for by the dynamic forces of the planet. It is its own meditation. I love how my body becomes reacquainted with itself in hot water. I love the contrast between hot water and cold air, the way steam and sweat become indistinguishable. My cheeks and skin soften; my muscles no longer tense from thoughts. I can see it in other people, too. Their eyes are less quick, their brows slack. No one ever seems to be in a rush at a hot spring.

Soaking is a singular human experience: it promotes presence, relaxation, and reflection. It removes pretenses and distractions. It gives us the opportunity to be a citizen of nature, ritual, and community. I’ve learned in my travels that each soaking experience is unique, tied to culture, traditions, and geography.”

Riemvasmaak Hotsprings | Image: © Greta Rybus

Image Caption: When thinking about a book about hot springs, I knew it was essential to include the story of Riemvasmaak Hot Springs and how it was at the center of South Africa’s first land reparations case. From my book, ‘Hot Springs”:

“The elders believe that this is a sacred place, a holy place,” said Henry Basson, who manages Riemvasmaak Hot Springs. “They come here to get rid of demons and evil spirits and even come down here to pray to connect with God. They believe the water has a lot of power.” That was the first thing he told me about this place. The second thing was about the day they were forced to leave.

“The day we were removed, it felt like the saddest thing that had ever happened in history,” he said. “They forcibly, forcibly removed us. Back then, we had quiver-tree houses, traditional houses made from plants. They took us out of our homes and set them alight, they would shout, ‘Everything out!’ They said we must grab our things, but we were so near the fire, we couldn’t get everything out. Everybody was crying, especially the older people.”

The forced eviction took place in 1973 and 1974, when the people of the Riemvasmaak were torn from their homes and driven to different parts of the region. Henry’s family was relocated to northern Namibia, sent there because of the language they spoke, Nama. For decades the land was occupied by the military, the landscape used primarily to train infantry to shoot and to practice unleashing bombs upon the land. The hot springs were cordoned off to be used only by members of the military; any visitors were escorted and monitored. In the 1990s, Namibia gained independence and Nelson Mandela was elected president of South Africa, and negotiations to return the land began. Riemvasmaak became South Africa’s first repatriated land when it was returned to the original owners in 1995.

Myvatn Nature Baths / Jarðböðin við Mývatn | Image: © Greta Rybus

Image caption: “Iceland often smells of geothermal water and steam; heavy, sulfuric, and metallic. I could smell it outside the airport, running in the municipal faucets, and in wafts along the roadside as I drove northward along the ring road. Over 85 percent of homes in Iceland are heated by geothermal energy, using turbines to capture the pressurized steam that results from precipitation trickling down to hot bedrock. Among the earliest of the island’s six power plants is the Bjarnarflag Geothermal Station, built in the late 1960s between the shores of Lake Mývatn and Námafjall Mountain. It generates 18 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity annually, creating a bright-blue alkaline runoff that pools at the power plant base, then is harnessed by the Mývatn Nature Baths for soaking and swimming.”

[…]

“In hot springs, you see all kinds of bodies and you see the bodies of strangers,” said Icelandic anthropologist Helga Ögmundardóttir. “Now that tourism has increased, you may see people from all around the world in an Icelandic hot spring. I mean, to see the half-naked bodies of others! That should be normal. Your body is irrelevant. Your body is your shelter for this life.” The hot spring is a place with a warm perspective of our bodies.”

About Greta: Greta is a full-time freelance photojournalist specializing in editorial portraiture, travel, and documentary photography. Born in Boise, Idaho, Greta studied Photojournalism and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Montana. Raised by schoolteachers who taught overseas, she has lived in Japan, the Netherlands, the San Juan Islands, Montana, Seattle, and the Sawtooth Mountains.

For four years, she had a goal to spend one month of every year living and photographing in a new place, exploring how climate change impacts individuals and communities. She worked on the project in Senegal, Panama, Norway, and Idaho. It deepened her interest in photographing restorative and meaningful connections to the natural world. She wrote and photographed a book: Hot Springs: Photos and Stories of How the World Soaks, Swims, and Slows Down, now available for preorder.

She is inspired by the cultures created by Dolly Parton, Pee-wee Herman / Paul Reubens, Tasha Tudor, Seinfeld, Beyoncé, Andrew Wyeth, Robin Wall Kimmerer, Bjork, Miss Rumphius / the Lupine Lady, Dorothea Lange, David Byrne, among others.

She is currently based in Maine where she lives with her partner, Zach, and their dog, Murray.

Learn more about her work, here.

Or to visit with her IRL on tour:

Book Signing, Rediscovered Books (Idaho) - April 20, 12:00 - 1:30